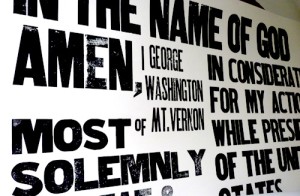

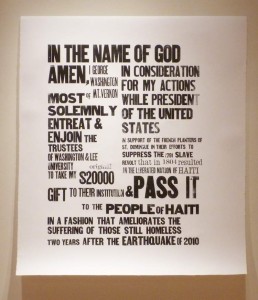

In the name of God, amen, I George Washington of Mount Vernon—a citizen of the United States, and one-time President of the same, having remained silent for these two hundred and eighty years, do on this 22nd day of February in the year 2012, in consideration for my actions while President of the United States in support of the French Planters of St. Domingue in their efforts to suppress the slave rebellion of 1791 which resulted, twelve years later, in the liberated nation of Haiti, now most solemnly entreat and enjoin the Trustees of Washington and Lee University, in the County of Rockbridge, in the Commonwealth of Virginia, to take my original gift of $20,000 to their institution and pass it to the people of Haiti in a fashion that ameliorates the suffering of those still homeless two years after the devastating earthquake of 2010. It is my ardent wish that this be accomplished without undue delay, notwithstanding the necessary assurances of due diligence.

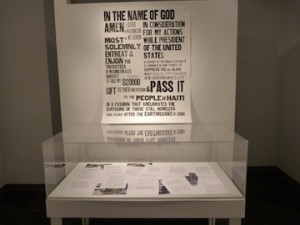

The above statement is the title of an artwork exhibited by Craig Pleasants at the Staniar Gallery of Washington and Lee University in a show entitled Volume -April, May, 2012.

The expanded artwork is on exhibit at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, February 12 – 27, 2013. It will include letters and communication between Pleasants and the students, staff and administration of Washington and Lee, and with Koneksyon Ayiti, the NGO that was to facilitate the construction of the houses. Some of that communication is below.

March 13, 2012

Dear President Ruscio,

With a solo show opening at Staniar Gallery in six weeks, I look forward to talking with you about the exhibit, in particular about the piece above that deals directly with Washington and Lee University and its Trustees. In the following letter, I hope to address any concerns and answer many of the questions that may arise from such a piece of art. This piece will be only one artwork among many others in the show which includes works on paper and a large sculptural piece.

The physical manifestation of this artwork will be a drawing, mostly black and white, incorporating the text. The conceptual and imaginative aspect of the artwork will encompass far more than its physical manifestation. In effect, the title of the artwork IS the artwork, a conceptual piece. In essence, the artwork is the myriad processes of discussion and negotiation inspired by the artwork, and in an ideal scenario, the accomplishment of the request. Ultimately, then, in addition to being a drawing, the artwork can encompass both the symbolic righting of an historical wrong and the actual amelioration of suffering for a small number of people. It could also encompass the relationship that ensues between the administration, students and faculty of Washington and Lee and NGOs in Haiti and the U.S. and the people they serve. Of course such an action on the part of an artist raises many questions.

In the following pages, I have attempted to address these questions and give you a sense of how I have worked to engage the broader University community. I realize that the time between now and the opening of the exhibition is limited, but even given the short timeline, there is great potential for this artwork to reverberate with positive effects throughout the Washington and Lee University community and beyond. I look forward to talking with you further about this project.

Sincerely,

Craig Pleasants

Historical background for the artwork In 1791, two years into the first term of the first U.S. President, there was an uprising of slaves on Saint Domingue, a French colony that was using slaves to produce goods for consumption in Europe and North America. Washington made the decision to send $750,000 in aid to the white French planters of St. Domingue to help them put down this slave rebellion. Because of this aid, the rebellion was suppressed for years, but never died. Twelve years later, in January, 1804, that rebellion finally succeeded, resulting in the liberated nation of Haiti, the first ever established by former slaves, and only the second liberated nation in the Americas. In 1796, George Washington was given a gift of James River Canal company stock from the Virginia Legislature worth approximately $20,000. Washington did not feel it was appropriate to accept the gift, yet did not want to slight the legislature, so he accepted the gift and gave it to the struggling Liberty Hall Academy, now named Washington and Lee University. My proposal is a symbolic gesture that atones for Washington’s act of supporting those who participated in the egregious institution of slavery, and of course, for Washington’s participation in the same at Mt. Vernon. At the same time, it becomes more than symbolic in that it actually addresses a desperate need, albeit for only a few families.

Why would an artist choose to do such an artwork? Although I began my academic career in politics in hopes of effecting social change, I came to understand that social change often comes about not through legislative fiat, but through a change in consciousness often facilitated through art and culture. So for thirty-five years, I have made artwork that speaks to the social realm, that deals as much with ethics as it does with aesthetics. Of course, this motivation is far from unusual. In fact, outside of the Western world, this social involvement is very often art’s normal function, but this motivation also has a long and respected history in the European tradition and among American artists. My work is in this tradition.

Why would Washington and Lee University want to participate in this artwork? This is the major question and one for which there are many answers. The overarching answer is that good art creates a ripple effect that moves out through a community, creating vibrancy and bringing people together in a positive way. Some of those ripples are considered here.

Honor. Ethics. Morals. One of the most important things a student takes away from his or her four years at Washington and Lee University is a sense of honor. In the narrative of the college, Robert E. Lee established the code of honor early on, the sense of being a “gentleman,” of doing the right thing, of acting with civility toward other people. This sense of honor is reflected in all aspects of life at Washington and Lee. The national narrative around George Washington is first and foremost, a similar narrative. He was a man of sterling character. We Americans believe that with all our hearts, and from the historical record, it actually turns out to be mostly true. Sadly, his narrative also contains the fact that Washington held other human beings in bondage. He also provided support to others who held human beings in bondage and those others were far more cruel in their dishonor and disrespect for the enslaved people. I am speaking of the French Planters of the West Indies, principally, of Saint Domingue, now Haiti. This is one of the few smirches on Washington’s otherwise exemplary life. My artwork gives a new voice to George Washington, allowing him to own up to his mistakes and to atone for them, something the historical record indicates he would do were he to magically reappear in 2012.

Educational and curricular benefit. In a way not unlike Washington and Lee’s brilliant Shepherd Poverty Program, this project can be approached from many disciplines. History. Politics. International Relations. Philosophy. Sociology. Business. Religion. Art History. Anthropology. Studio Art. Seized thoroughly, this project offers an opportunity for students to engage in real-world problems alongside professionals from NGOs in the United States and Haiti, relating their experiences back through the disciplines, and relating their education to the world around them. Aside from specific disciplines, the project also opens the possibility of intellectual exchange about subjects such as philanthropy, poverty, honor, and social justice.

Race relations. I know from my four years experience as a Washington and Lee parent and from subsequent conversations with its constituents, that despite the narrative of honor, there is yet hovering over the college a small cloud on the issue of race and the dishonor with which black people were treated in Virginia and even by the University’s namesakes. How does an institution of this stature confront this issue? I am sure this is a question that you have thought about much more deeply than I. This artwork offers a way to admit to a tarnished past and to atone for it, and does so in a way that does not cast blame or dishonor, but rather asserts a desire to make amends. This offers an opportunity for Washington and Lee in a local arena and on a national stage.

Public relations. Should Washington and Lee University undertake the magnanimous gesture of passing on George Washington’s gift in this way, that gesture has the potential to generate positive publicity on a national scale. Were the University to wish to reach a national audience tying the institution so definitively to George Washington, while at the same time tying it to honor and a profound sense of ethics, it would be necessary to spend $20,000 many times over.

Development. I have worked for thirty years in the non-profit sector, including stints as executive director and chief development officer for arts organizations and so I understand development is always a concern for a non-profit, even one as well-endowed as Washington and Lee. I also understand that connected to the opportunity for publicity is the opportunity for cultivation and development. Were I an alumnus (I am the parent of an alumna) of Washington and Lee, such an action on the part of the institution would make me very proud and inspire me to become more closely affiliated with the institution. I can only imagine that passing on George Washington’s $20,000 gift in this way would result in gifts to the institution far far exceeding that figure. That being said, this raises an issue that is of great importance to this project. It is the issue of “gift.” If one gives a gift in the truest sense of that word, one does not expect anything in return. For this project to be truly successful, the University should make this a gift free and clear, from its own resources. This project does not request that a group of students or faculty or administration go out and raise this money. That would be counter to the spirit of the project and would be counter-productive, in my experience, to real development. Therefore, this gift is something that should come from the Trustees of the University in the same spirit that George Washington gave it to their counterparts in 1796: as a gesture of goodwill for those less fortunate, but ideally this should be a gift given in the spirit of atonement. It should be done in recognition of the fact that George Washington, as great a man as he was, was not a perfect human being. His gift to Liberty Hall Academy was evidence of his sterling character –he felt unable to receive a gift for something he had done as a public servant. But before he made that gift, he had not only held other human beings in bondage, he had used money from the pockets of American taxpayers to support to a group of people who were far and away more cruel in their administration of the institution of slavery, the planters of St. Domingue.

What are the practical concerns? Over the course of the last few weeks, I have talked with many stakeholders at Washington and Lee, assessing the interest in the project and how to move it forward with the participation of aspects of the University. One of the first people I reached out to was Harlan Beckley because I remembered him as President of the University when my daughter Julia was there and I remembered being deeply impressed with the Shepherd Poverty Program. Harlan’s generosity has been remarkable. He instantly responded to my email requesting a meeting with him and listened intently to what I proposed, even though, in our first meeting, the idea was ill-formed and admittedly, a bit shocking. He has given counsel, met with students to get their input, and has asked many good questions along the way.

Likewise, Clover Archer Lyle has been open and supportive to this proposal. She has supported my inquiries and helped make connections at the University. Clover and Harlan have posed a thorough series of questions about the nuts and bolts issues involved with the implementation of this project including relationships with NGOs in Haiti and the U.S. and I have a likewise thorough series of answers. I am happy to share this information with you in a later communication.

I have talked with R.T. Smith, the Editor of Shenandoah to discuss ways that Shenandoah could be used to expand the conversation around this topic. I have also been in communication with Professor of History Ted Delaney who expressed interest in participating on some level with the project. I have asked him to write a short piece about the historical context of Washington’s support of the planters in Saint Domingue and about Washington’s gift to the University. I have also spoken with Kathleen Olson, a faculty member in Studio Art, Christina Lawrence, a senior Art History major with a minor in Shepherd Poverty Program, Kathryn Marsh-Soloway, a junior Art History major with a minor in Shepherd Poverty Program, and Dana Fredericks, a senior Engineering major and W&L liaison to Engineers without Borders.

There are many doors leading out of the structure that is the idea of this artwork and many ways for other people to be involved.